In this week’s parashah, God tells us that life and death, blessing and cursing, are placed before us, and that we should choose life so that we and all of our children and our children’s children shall truly live (Deuteronomy 30:19).

Living and Dying

God places blessing and cursing right in our face and the power to give and take life with just who and how we are, the look in our eyes and our facial expression or smile, and through how we see ourselves and one another.

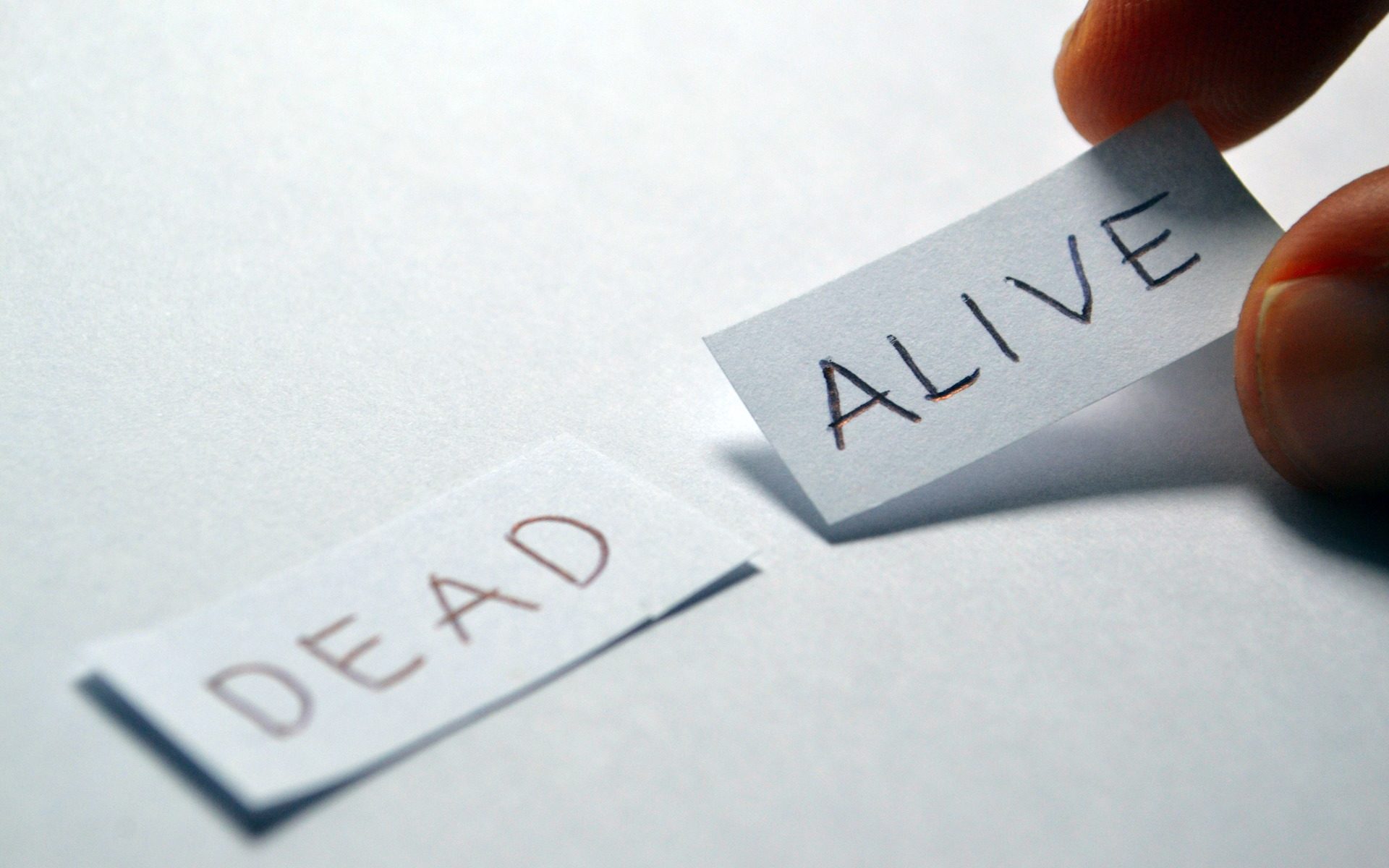

God places before us life and death and asks us to choose. God places before me and before each individual person living and dying and begs me, you, and us to choose living. When we choose life, we choose to live and to enliven our life and those of others. Only then do we—only then can we—truly become alive.

We live in a wonderous world with technological innovations unimaginable to our ancestors, our grandparents, or even our parents and older siblings. We are placed in a world with many blessings and many curses—a world where communication does not take years, months, or weeks but occurs across the globe in barely an instance.

We are placed in a world where machines operate farms and factories, the furthest reaches of our galaxy are often precisely observed and measured, and in a world where science, not God, heals. We live in a world that will be entirely unrecognizable to our children and completely beyond our wildest imaginations, hopes, and dreams.

Yet, we cannot or ever live in a world where we transcend physical life and biological death. It is God—it is the Sacred Divine—that places blessing and cursing before our eyes, life and death right on our lap.

The Beauty of No Escape

No matter how advanced our science, medicines, and technologies, we cannot escape the fact and reality that we are beings like all creation who are born and who die. No matter how invincible we are—or think we are—we are vulnerable creations. We cannot escape pain or suffering, heartbreak or illness, or most especially, death.

Then why would God in this week’s parashah tell us that there is life and death always in front of us before our very face, and that we should choose life so that we may live? Do we really have a choice? It is not like we can choose to live forever! Death will always find us! Without exception! Or is there a way to choose life, and to live?

This is the choice we have. Do we choose blessing or cursing? Life or death? When we suffer and ache and hurt, and the world around us, between us, and within us is hurting and on fire, why is this so? Why do we suffer? And what do we do about it all?

Suffering and Compassion

This quarter, I am taking a course on “The Problem and Evil and Theodicy” at the Pluralistic Rabbinical Seminary taught by one of the school’s founders, Rabbi Patrick Beaulier. It is not a required class, though it is a required life activity. There is no greater question than, “Why do we and others suffer?” How do we respond? And how must we respond?

According to Rabbi Patrick, theodicy relates to the “problem of evil” and “reconciling the idea of a Good god with suffering of some kind”. He teaches that “theodicy is about this reconciliation of the problem of evil” and cautions us not to make this into a mere academic or theological exercise, but to realize that this work is “practical”, an integration of theology and “how to think about the nature of the Divine and how to work with other people particularly in times of suffering.”

Rabbi Patrick adds that theodicy is “about the courage to face suffering…. Theodicy… really comes out of a human question, ‘How do we persevere in the face of cruelty and wrong?’”

If I were to put Rabbi Patrick’s ideas in my own language and words, I would say that serving others begins with knowing the Divine and our unique, subjective, and common experience of suffering.

The Problem of “Evil”

Rabbi Patrick outlines three varying versions of similar presenting problems of evil and theodicy. Essentially, if God exists, created the world, and is omnibenevolent, omnipotent, and omniscient—or put more simply: all-good, all-powerful, and all-knowing—why would evil exist? And why would God not prevent evil from existing in the world? And let it harm us?

According to Rabbi Patrick, there are five common types of evil that theologians—or perhaps we all, as humans—come across.

The first one is “moral evil”. This is where a person does something “evil” of their own free will and volition. A common example of this might be Hitler and all that transpired during the Holocaust and World War II.

The second common type of evil is “natural evil”. This is the harm or “evil” done by animals or nature where there is no volition or intent to cause harm or suffering. Some examples of this might be hurricanes and other natural disasters, or one animal hunting and feeding off of another.

The third common type of “evil” is “judgments from God”. This is the harm or “evil” done by God that is somehow deemed “justified”. Examples of this might be curses and plagues, like the ones hurled at Pharaoh and the Egyptian people during the time of the Exodus.

The fourth common type of “evil” is “demonic”. This is the “evil” done by the demonic or evil spirits. An example of this might be the grim reaper or Angel of Death.

The last and fifth common type of evil mentioned by Rabbi Patrick is hester panim, or the hiddenness of God’s face from us, even as a punitive measure. An example of this might be God’s presumed inaction in the face of the Holocaust.

The Problem of “Good”

Yet, all of these three types of presenting problems for theodicy and five common types of evil discussed and philosophized about throughout Western civilization presume something in common. It assumes an idea of God—one that I do not accept—a conception of the inconceivable and in some way even a violation of our deepest humanity and our deepest essence of Divinity.

The Judeo-Christian tradition—or at least the most superficial parts of it—assume a God who is all-good, all-powerful, and all-knowing. Yet, can this be so? Are the most extraordinary grandeurs of the universe and most detailed, intricate aspects of my or your most personal, intimate life, controlled and planned by a deity like a puppet master does their puppet? Or a clockmaker their clocks?

The Book of Genesis, our primordial story, describes God as creating humanity—male and female—in their image (Genesis 1:27). Yet, in reality, is the Divine creating us in their image, or is it we who are creating the Divine in ours?

We all want the same things, human and Divine alike. We all want to be seen, to be recognized, affirmed and supported, loved and cherished in the most ordinary and personal ways, especially by those whom we care for the most, depend on the most, and are most vulnerable to and dependent upon.

For me, this is what the Tanach, or Bible, is about. This is what can be spoken about on one foot. The Bible—like life—is the torrid and gracious love story of humanity and Divinity. The Bible—like life—is a beautiful love story between what is most ordinary and extraordinary; acceptance of a God who is closer to us than even our own jugular vein—as the Quran (50:16) teaches—and a God who is beyond conception or rational understanding. The Bible—like life—is the love story of blessing and cursing, good and evil, living and dying.

Does good exist? Yes. Does evil exist? Yes also, when seen in a certain way. Does God exist? As sure as your eyes are reading this text now.

How do you choose? How do you not?

Evil—a troublesome word, if used at all—is not the actions of a rogue God, messenger somehow of God, or God’s creation, but rather a verbal expression and human label for the hurt and betrayal we come in contact with when we experience ourselves or others violating our deepest essence, perfect and imperfect all the while.

As Shunryu Suzuki Roshi, one of the 20th century founders of American Soto Zen Buddhism and the San Francisco Zen Center, says, “Nothing we see or hear is perfect. But right there in the imperfection is perfect reality…. Each of you is perfect the way you are… and you can use a little improvement.”

In this way, we are all capable of the greatest good. And we are all capable of the greatest evil. We are the angels of God, and they are we. And, I am Hitler, and he is also me.

Why does evil happen? Evil happens. Why does good happen? Good happens. Why does God happen? God happens!

It is so terribly hard being you! And no greater joy! The sacred Divine places within us, in front of us, and between us, both blessing and cursing, both good and evil, living and dying. How do you choose? How do you not?

Next Steps

As always, if you are interested in learning more about Jewish Mindfulness Meditation or how to create a more meaningful spiritual path for you and your loved ones, please make sure to sign up and click the “Stay Connected Now!” button below!

Mindful Judaism is pleased to offer daylong Jewish meditation and mindfulness retreats, shabbatons (weekend workshops), and other live and in person events throughout California and beyond.

If you are interested in bringing Mindful Judaism to your community, synagogue, or meditation group, please contact us at adam@mindfuljudaism.com for more information and to make arrangements.

Adam Fogel

www.mindfuljudaism.com

I found myself eagerly reading this post. I learned a lot, and it made me think about life, Judaism, the choices that we have (and I have) and above all – faith. We can accept suffering as a part in our life, maybe even to learn how to live with the pain and sadness, but we also have the choice to decide to do more than just exist.